CAMDEN, NJ – I was born in the hold of a slave ship soaked in urine and feces whose name history did not bother to record. I am a Foundational Black American. For more than three hundred years, I have walked this land, a reluctant witness to a relentless paradox: the nation of lofty ideals built upon a foundation of profound, sustained cruelty. The question that haunts my long memory is not for the brutal racist/white supremacist monsters, but for the others—the “good white people” in every era.

How the fuck did you stand by and watch?

This is the essential inquiry of our present. For in understanding the mechanics of that historical complicity, we find a stark blueprint for today’s crisis. Yet something fundamental has shifted. The distance that enabled your ancestors’ silence has been obliterated. Today, the plea is not just for action, but for sight—to finally, fully see our humanity.

The Machinery of Acquiescence, Then and Now

The “good White folk” of any era rarely believes themselves complicit. They operated within a system of convenient distances.

How did you watch us be enslaved? You told yourselves it was an economic necessity. You saw the auction block from afar, heard the wails as a faint echo, and were comforted by sermons claiming we were not fully human. That distance was your insulation.

How did you witness the systematic rape on plantations? You chose not to see the high yellow children running through the fields. The violence was rendered invisible by a conspiracy of silence, the resulting children used as proof of our “depravity” rather than your community’s crime.

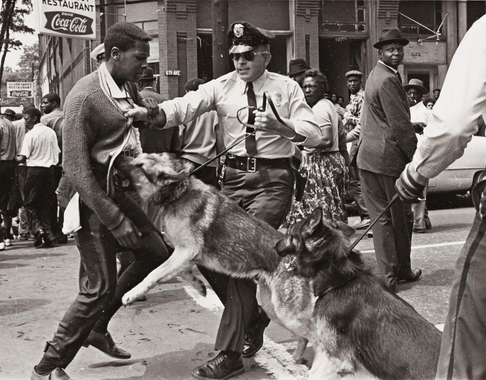

Today, the distance is gone. You cannot claim you did not see George Floyd’s life pressed from him for nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds. You cannot say you did not hear the fear in a child’s voice separated from her parents at a border you politicize. The camera phone is the unblinking eye my people never had. It has made the abstract, concrete. The historical buffer is broken.

The Fear Beneath the Silence

I have lived long enough to sense the tremor beneath the surface of this nation’s psyche. I must acknowledge what I believe fuels much of the backlash, the frantic rewriting of history, the cries of “replacement”: a deep-seated, often unspoken fear that Black and brown people, given the levers of power, will treat you as you have treated us.

For three centuries, you have shown us the blueprint of vengeance. The whip, the law, the noose, the gerrymander—all tools of subjugation. It is a terrifying legacy to contemplate. So you must hear this, clearly: We do not seek your destruction. We seek a transformation of the system built for it. We seek a democracy where no group holds permanent dominion, because such dominion inevitably corrupts and always, always visits violence upon the powerless. The multiracial democracy we strive for is not your nightmare of reversed oppression; it is the only possible escape from the nightmare you yourselves created.

The New Witness and the End of Gaslighting

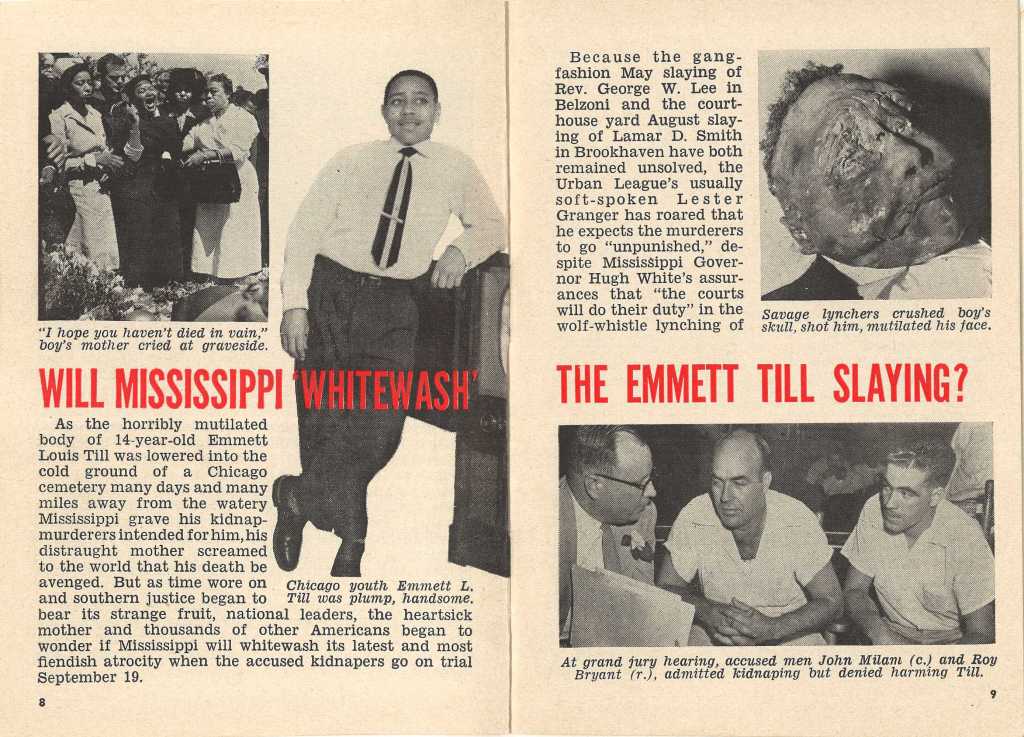

When the Supreme Court ruled we had “no rights,” your ancestors could dismiss it as distant legal theory. When Rosewood and Tulsa burned, they could be framed as “riots.” When Emmett Till’s murderers were acquitted, the lie could be upheld as the law.

Today, the gaslighting fails against the evidence in our hands. We witness, we record, we share, we archive—instantaneously. We can juxtapose the “law and order” rhetoric with the violent repression of a peaceful protest. We can contrast the paeans to “heritage” with the footage of a neo-Nazi march. The dissonance is laid bare. To be a passive spectator now is not a failure of information, but a conscious choice of morality.

A Way Forward: From Spectators to Co-Creators

The path forward is not found in a return to a civility that never included us. It is forged in the active, courageous construction of a true multiracial democracy. This requires more than your guilt; it demands your partnership.

First, you must believe your own eyes and ears. Trust the testimony streaming from our phones, our communities, our lived experience over the sanitized myths of comfort.

Second, you must relinquish the fear that equity is your loss. A democracy where a Latina’s vote counts the same as a white farmer’s, where a Black child’s history is taught as thoroughly as a president’s, where a Native nation’s sovereignty is respected, is a stronger, more just, and ultimately safer country for everyone.

Finally, you must move from sentiment to structure. It is not enough to decry racism; you must defend voting rights, support truthful education, and challenge inequity in your neighborhoods, councils, and boardrooms. The MAGA movement gambles on your eventual acquiescence, your retreat into comfort.

My three centuries whisper that this is the decisive hour. The tools of witness we now possess have shattered the old alibis. You can no longer claim you did not see, did not know. You can only choose what you will do now that you have seen.

See our humanity, not as an abstract concept, but in the terrified face of a man under a knee, in the determined eyes of a child walking into a newly integrated school, in the grief of a mother at a grave. Then, act from that sight. Build with us a democracy worthy of its name, not as spectators, but as co-creators. The silence of your ancestors was permission. Your voice, your vote, your unwavering alliance must now become the foundation of something new.