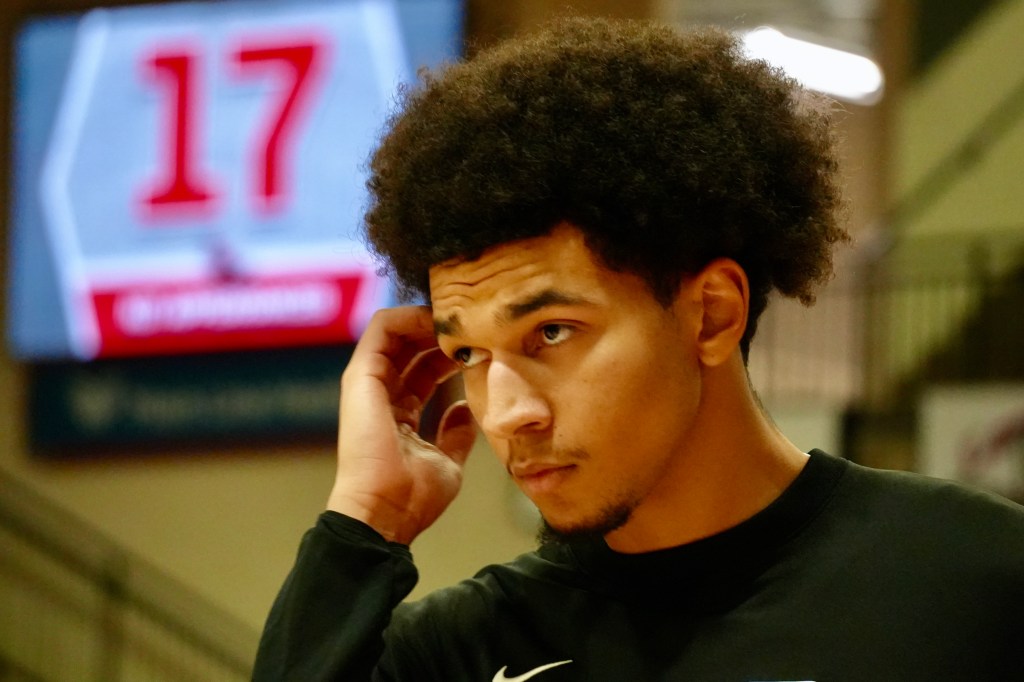

PHILADELPHIA, PA – In the burgeoning industry of college basketball, where the transfer portal spins faster than a full-court press and name, image and likeness deals have rewritten the economics of amateurism, the career arc of a player like Derek Simpson offers something increasingly rare: a coherent narrative. It is a story not of dissatisfaction or chasing a bag, but of strategic foresight. It is a case study in how a young athlete, facing the cold calculus of roster construction, can reclaim his trajectory by understanding that sometimes, the smartest move is a lateral step designed to launch a vertical rise.

Simpson, a 6-foot-3 guard from Lenape High School in Burlington County, N.J., arrived at Rutgers as a three-star prospect, ranked as high as seventh in the state and 44th among point guards nationally by ESPN. He was known as a quick, decisive playmaker and a tenacious on-ball defender—traits forged, under the tutelage of Kyle Sample and Lonnie Lowry in the crucible of the Adidas 3SSB Circuit with the K-Low Elite Basketball Club, where he faced national-level competition. The son of a Division I player, Simpson understood the game’s demands. He was ready to contribute immediately, and he did, playing 20.1 minutes a night as a freshman and expanding his role to 26.0 minutes as a sophomore, averaging 8.3 points and 2.9 assists.

Then the tectonic plates of recruiting shifted under his feet.

The Calculus of a Crowded Backcourt

On December 6, 2023, Dylan Harper, a consensus five-star combo guard and the No. 2 overall prospect in the 2024 class, committed to Rutgers. It was a seismic win for the Scarlet Knights, a program-defining moment that brought a potential one-and-done lottery pick to Piscataway. But for Derek Simpson, it presented a stark reality. In the modern game, a player of his profile does not merely compete with a talent like Harper for minutes; he competes against the gravitational pull of a franchise player’s usage rate. The math was simple: there would be fewer touches, a diminished role, and a shrinking canvas on which to paint his professional aspirations.

Simpson’s subsequent decision to enter the transfer portal was not an act of flight, but of portfolio reallocation. In an environment where players must weigh short-term financial incentives against long-term career risk, he made a calculated bet on himself. He opted out of the volatility of a diminished role in the Big Ten and placed his assets in a high-growth opportunity: the Atlantic 10 and St. Joseph’s University. It was a move that prioritized developmental infrastructure and on-court equity over the simple prestige of a conference logo.

The Platform and the Coach

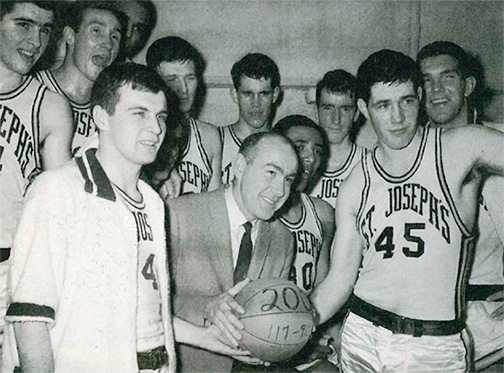

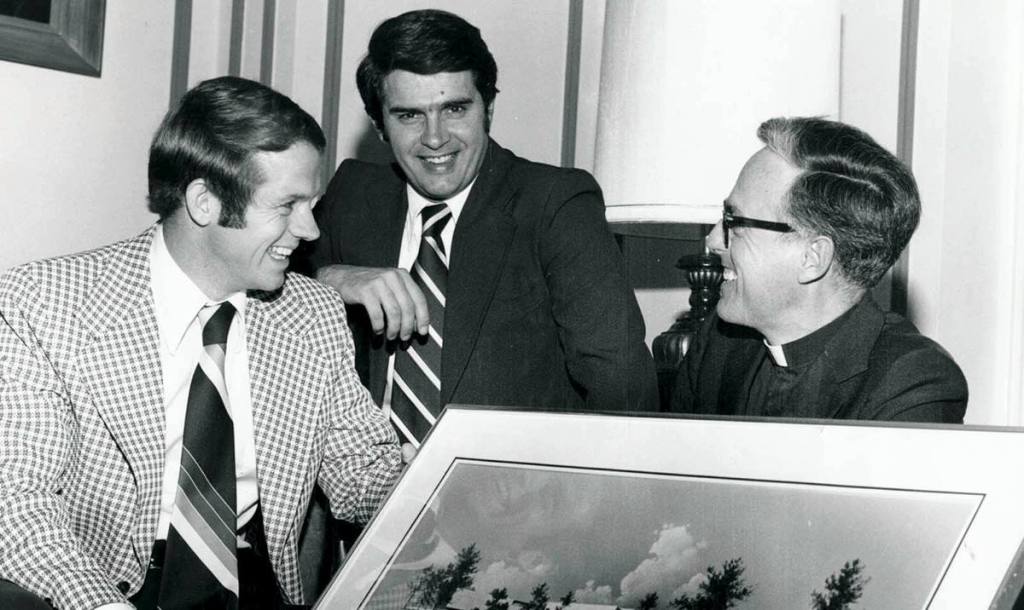

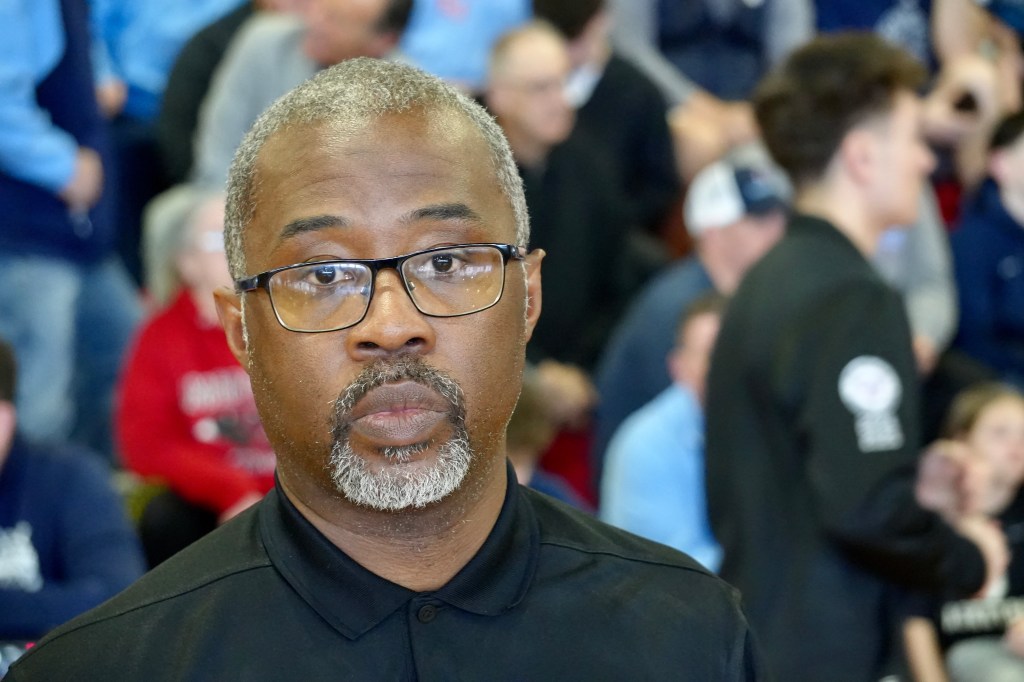

If the decision to transfer was the strategic investment, the choice of St. Joseph’s was the blue-chip stock. The Hawks, under the guidance of Billy Lange, had built a reputation for player development. But when Lange departed suddenly for an assistant coaching position with the New York Knicks, the program turned to Steve Donahue. In a season defined by coaching flux, Donahue steadied the ship with the steady hand of a veteran tactician. He was subsequently named Atlantic 10 Coach of the Year, a testament to his ability to maximize his roster.

For Simpson, Donahue’s arrival was serendipitous. Donahue recognized that Simpson’s greatest asset—his decisive, attacking mentality—needed freedom, not restraint. Rather than forcing him into a rigid system, Donahue built actions around his penetration, allowing Simpson to play to his strengths. St. Joseph’s needed a leader; they got one who had been waiting for the opportunity to lead. The Hawks finished the regular season 21-10 overall and 13-5 in the A-10, good for third place. Simpson was named First Team All-Conference. The platform had delivered.

Rejuvenation and the Path Forward

The A-10 has long been a league that rewards guard play, a proving ground where skill meets opportunity. Simpson thrived in that environment. Freed from the shadow of a generational talent, he demonstrated the full spectrum of his abilities: the quick first step, the defensive pressure, the playmaking vision that had been honed since childhood. He did not merely accumulate statistics; he engineered victories. His professional aspirations, which risked stagnation in a diminished role at Rutgers, were not just rejuvenated—they were amplified.

A Blueprint for the New Era

Derek Simpson’s journey is a persuasive argument for agency in an era of uncertainty. He understood that remaining at Rutgers, while comfortable and familiar, carried the risk of becoming a schematic afterthought. He recognized that the value of a player is not solely determined by the conference in which he plays, but by the role he occupies within it. By transferring to St. Joseph’s, he found a coach in Steve Donahue who needed his talents and a league that showcased them.

In the end, Simpson’s story is not about what he left behind, but about what he correctly anticipated he could become. It is a reminder that in the complex economy of modern college basketball, the most valuable asset a player can possess is not a highlight reel, but a clear-eyed understanding of where his skills will be valued most.

The Pro Comparison — Finding the Stylistic Parallel

Identifying a professional comparison for Derek Simpson requires looking beyond simple physical measurements and instead focusing on archetype, skill set, and role projection. Simpson is not a primary creator in the Jalen Brunson mold, nor is he an undersized two-guard. He occupies a specific niche: the secondary playmaker who initiates offense, pressures the ball defensively, and operates with a decisive, attacking mentality.

The NBA Comparison: A Prime Cory Joseph / Jevon Carter Hybrid

The most apt NBA comparison for Simpson is a fusion of Cory Joseph (in his prime Indiana/ Sacramento years) and Jevon Carter. Here is why this parallel holds:

The Cory Joseph Elements:

Joseph built a decade-long NBA career as a steady, low-mistake point guard who could play on or off the ball. At 6’3″, he lacked elite burst but compensated with strength, timing, and a high basketball IQ. Simpson mirrors this in his decision-making—note the single turnover in that signature Richmond upset, a game where he also logged 37 minutes and grabbed 13 rebounds . Like Joseph, Simpson understands that his value lies in limiting negative plays while applying consistent defensive pressure.

The Jevon Carter Elements:

Carter built his NBA reputation on being an absolute nuisance defensively while providing spot three-point shooting. Simpson’s on-ball defensive tenacity—honored in the original scouting report—echoes Carter’s relentlessness. However, Simpson has shown a superior ability to rebound for his size (5.7 rebounds per game as a senior, including that 13-rebound outburst) . The three-point shooting remains the variable; like Carter, Simpson’s percentage can fluctuate (27% as a senior, but with hot streaks like the 5-7 performance) .

The International Comparison: A French League Star Archetype

If the NBA path proves narrow, Simpson projects as a standout in top European leagues, specifically the French LNB Pro A or German BBL. His game resembles a composite of veteran American guards who thrive overseas: the ability to control tempo, defend multiple positions, and score in bunches without needing isolation possessions. The 9-assist game against Dayton is particularly instructive—it reveals a playmaking vision that was often suppressed in his Rutgers years . In Europe, where team structure and defensive discipline are paramount, Simpson’s low-turnover, high-pressure style is a luxury commodity.

Mock Draft Profile — Derek Simpson

Position: Point Guard / Combo Guard

Class: Senior

School: St. Joseph’s University

Height: 6’3″

Weight: ~190 lbs (estimated)

Age: 22

Prospect Overview

Derek Simpson enters the 2026 draft cycle as a classic “late bloomer” whose trajectory was temporarily suppressed by circumstance before exploding at the appropriate level. After two seasons at Rutgers where he showed flashes (8.3 PPG, 2.9 APG as a sophomore) but faced a diminishing role with the arrival of Dylan Harper, Simpson transferred to St. Joseph’s and revitalized his career. He leaves college as a First Team All-Atlantic 10 selection, having led the Hawks to a 21-10 record and a third-place conference finish.

Simpson’s appeal to professional teams lies in his clarity of role. He knows exactly what he is: a decisive, quick-twitch playmaker who defends with tenacity and makes winning plays. He is not a volume scorer who forces offense, but a pressure-release valve who can create for himself and others when the defense collapses. His experience on the Adidas 3SSB Circuit with K-Low Elite prepared him for this moment—he has been competing against high-level competition for years and carries none of the deer-in-headlights tendencies that plague many mid-major prospects.

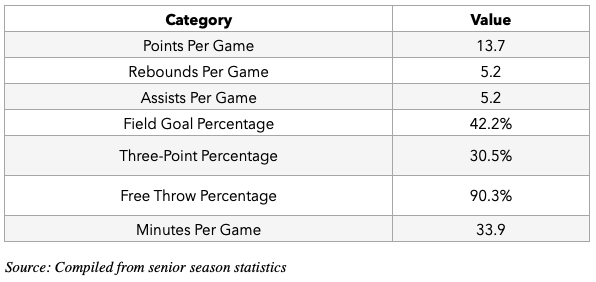

Statistical Snapshot (Senior Season)

Strengths

- Decision-Making Under Pressure: Simpson’s assist-to-turnover ratio tells only part of the story. Watch the film: he makes the right read consistently, whether attacking off a ball screen or kicking to a shooter. The 9-assist, low-turnover games are not anomalies; they are the product of a point guard raised by a Division I father and forged in competitive grassroots basketball.

- Defensive Versatility: Simpson’s lateral quickness allows him to stay in front of most point guards, while his strength enables him to switch onto larger wings in a pinch. He is the type of defender who disrupts timing simply by existing in the opponent’s space.

- Rebounding from the Guard Spot: At 6’3″, Simpson’s 5.7 rebounds per game—including a 13-rebound performance against Richmond—indicate a nose for the ball and a willingness to do dirty work. This translates directly to the next level, where guards who rebound are valued as “winning players.”

- Free Throw Shooting: A 90.3.% mark from the line suggests that the three-point shooting inconsistency is correctable. Players who shoot this well from the stripe typically have the mechanical foundation to improve their deep accuracy with NBA coaching.

Areas for Improvement

- Three-Point Consistency: The 30.5% mark as a senior is the glaring flaw. Simpson has shown the ability to get hot (5-7 against Richmond), but he also endures cold stretches where his mechanics waver . Professional teams will need to see a more reliable catch-and-shoot stroke to keep defenses honest.

- Shot Selection at the Next Level: Simpson’s mid-range game is effective in college, but the NBA and top European leagues increasingly demand rim pressure or three-point attempts. He must refine his shot diet to eliminate inefficient looks.

- Creating Separation Against Elite Athletes: At the high-major level, Simpson occasionally struggled to create space against longer, more explosive defenders. While he dominated the A-10, the gap between that league and the NBA is vast. He will need to develop counters—floaters, step-backs, pace changes—to compensate for any lack of elite burst.

Draft Projection

NBA: Late Second Round / Priority Undrafted Free Agent

International: Guaranteed Contract in Top-Tier European League (France, Germany, Spain)

Simpson is unlikely to hear his name called on draft night, but he is precisely the type of player who signs a two-way contract within hours of the draft’s conclusion. His combination of defensive readiness, decision-making, and positional size fits the archetype of the “three-and-d” guard, provided the three-point shooting stabilizes. Teams like the Miami Heat or San Antonio Spurs—franchises known for maximizing guards with his profile—should have him on their summer league radars.

The Verdict

Derek Simpson made a calculated bet on himself by leaving Rutgers, and that bet is about to pay dividends. He identified a platform—St. Joseph’s, the A-10, Steve Donahue’s system—that would showcase his complete skill set rather than bury him in a crowded backcourt. The result is a professional trajectory that now includes legitimate options: a two-way NBA contract, a lucrative European deal, or a training camp invite with a chance to stick.

In an era where prospects are often over-drafted based on high school rankings, Simpson represents the opposite: a player whose value is best measured not by where he started, but by where he finished and how he got there.