PHILADELPHIA, PA – To watch Shedeur Sanders play quarterback—with his pre-snap poise, his audacious no-look passes, his celebrated, unflappable “Shedeur Face”—is to witness more than a talented athlete. It is to observe a cultural reclamation project. His overwhelming support within the Black community, often chalked up simplistically to his confidence and swagger, is rooted in something far deeper than style. It is a profound, collective recognition. It is the applause of a community that sees in his assured success not just one man’s triumph, but a symbolic redress of a brutal, systemic history—a history whose scars are woven into the very DNA of Black American experience.

The Foundation: American Apartheid on the Playing Field

That history is an American Apartheid, a regime of exclusion not confined to the Deep South but sanctioned at the highest levels of national life, including the playing fields. From its inception in 1906 through the early 1970s, the NCAA operated as a gentlemen’s agreement for segregation, formally barring Black athletes from member institutions, particularly in the powerhouse conferences of the South. For seven decades, the Paul Robesons, Jackie Robinsons, and Jesse Owenses were brilliant, solitary exceptions proving a cruel rule. The Civil Rights Movement forced the gates open, leading to the rapid “tanning” of revenue sports by the 1980s. But the institutional response was not embrace, but a strategic recalibration of exclusion.

The Bureaucratic Barrier: When “Eligibility” Became the New Gate

When blatant segregation became illegal and immoral, the mechanisms of denial became bureaucratic. The NCAA’s evolving “initial eligibility” rules—Proposition 48, the Core Course requirements, sliding GPA scales tied to standardized tests—were weaponized as a more nuanced gate.

Legends like Georgetown’s John Thompson II and Temple’s John Chaney, towering figures who used their platforms without apology, called this what it was: racism. “The NCAA is a racist organization of the highest order,” Chaney declared in 1989, framing the rules as a new punishment for Black kids already punished by poverty. Thompson saw the cynical cycle: athletes were used as integration’s pawns under the guise of benevolence, then discarded with the same paternalistic logic when their numbers grew too great.

The Instinctual Knowledge: A Community Remembers What Was Lost

This is the buried trauma in the collective memory of Black sports fandom. It is the instinctual knowledge that for every Shedeur Sanders lighting up a Power 5 stadium today, there were countless Willie “Satchel” Pages, “Bullet” Bob Hayeses, and Doug Williamses of yesteryear who were denied the stage, their stats relegated to the glory of HBCU lore, their professional careers delayed or diminished. It is the understanding that the path was not cleared, but grudgingly conceded, inch by contested inch.

This brings us back to Shedeur. His journey is a direct rebuke to that entire historical project of exclusion.

Shedeur as Historical Agency, Not Just Athletic Talent

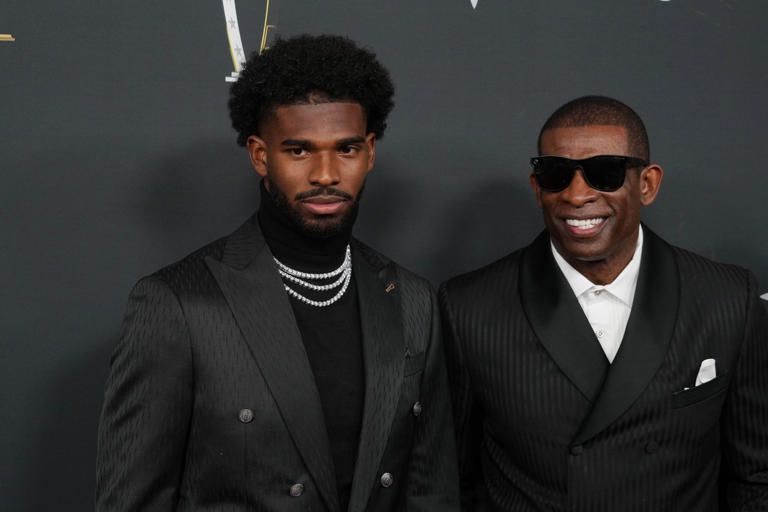

He began not at a traditional blue-blood program, but at Jackson State University, an HBCU, under his father’s tutelage. There, he didn’t just play; he dominated, showcasing a talent so undeniable it forced the mainstream to look to the HBCU, reversing the decades-long drain of talent from them. His subsequent transfer to Colorado and his record-shattering performance—37 touchdowns, 4,134 yards, Big 12 Offensive Player of the Year—wasn’t an assimilation. It was an annexation. He carried the HBCU-developed swagger into Boulder and made it the epicenter of college football.

His confidence, therefore, is read by the Black community as more than personal bravado. It is historical agency. It is the embodiment of a truth: “You could not keep us out forever, and now that we are in, we will not perform with grateful humility. We will excel with the unmistakable flair of those who know the cost of the seat we now occupy.” His much-discussed “swagger” is the posture of liberation from the historical narrative of being the excluded, the regulated, the “problem” to be managed by NCAA legislation.

The Echo in the Draft: A Familiar Story Reinforces the Bond

The fact that his prolific college career culminated in a fifth-round NFL draft pick—seen by many as a slight given his production—only reinforces the narrative. The community, schooled by history, sees the echoes: the subtle devaluation, the search for flaws in the Black quarterback, the institutional reluctance to anoint him the franchise cornerstone his college play warranted. Yet, even in that perceived slight, the support does not waver; it intensifies. Because the story is no longer about what the gatekeepers decide. It’s about what Shedeur, and by extension the community that sees itself in him, has already proven.

An Unfinished Battle, and a Symbol of Its Progress

The contemporary NCAA debate continues, now often couched in the softer language of “unintended consequences” for minority students, as noted by groups like the National Association for Coaching Equity and Development. But the shift from Chaney’s and Thompson’s explicit charges of racism to today’s milder objections itself tells a story of a battle partly won, yet ongoing.

Shedeur Sanders walks onto the field bearing the weight and the defiance of that unfinished battle. The Black community’s embrace is a celebration of his individual talent, yes, but it is also a collective, cathartic affirmation. It is the joy of witnessing a grandson of American Apartheid not just cross the forbidden line, but do so with a dismissive wave, a nod to the crowd, and a perfect spiral into the end zone. His confidence is their vindication. His swagger is their memory, weaponized, and set free.