CAMDEN, NJ – To understand Donald Trump, to truly grasp the fervor of the “Make America Great Again” movement, requires a confrontation with a deeply unsettling but irrefutable historical truth: Trump is not an aberration, but an archetype. He is the contemporary embodiment of a classic American figure, whose political power flows directly from the nation’s oldest and most potent strain—a white supremacist ideology that has been intertwined with concepts of democracy and liberty since the nation’s founding. On one hand, the anguish felt by many white Americans today as they witness the MAGA movement’s explicit racism is the anguish of a myth being shattered, the painful awakening from a national narrative that has systematically obscured this foundational reality. Black people, on the other hand, have lived through this movie since 1619.

The Indelible Thread: From Frontier to Empire

The doctrines that birthed the American nation-state were, from their inception, racial in character. Manifest Destiny, the Monroe Doctrine, and the White Man’s Burden are not separate chapters but sequential verses in the same epic poem of Anglo-Saxon supremacy.

Manifest Destiny, framed as a divine mandate to “overspread the continent,” was a theological and racial justification for genocide and land theft, casting Native Americans as “merciless Indian Savages” and Mexicans as obstacles to a providentially-ordained white nation. This was not mere expansion; it was ethnic cleansing codified as national mission. Historical records reveal a staggering decline from an estimated 5-15 million Native Americans prior to 1492 to fewer than 238,000 by the close of the 19th century. This represents a population collapse exceeding 96% over four centuries, driven by a combination of warfare, displacement, and disease, all facilitated by racist/white supremacist government policies.

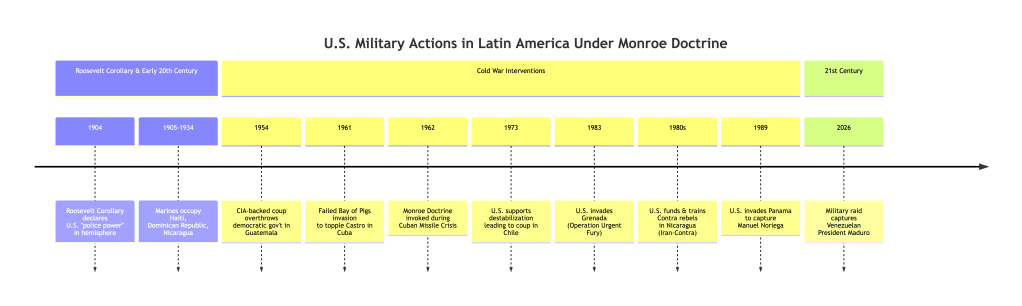

The Monroe Doctrine established the Western Hemisphere as a U.S. sphere of influence, a policy enforced not through diplomatic parity but through a paternalistic belief in the racial and political superiority of the United States over its non-white neighbors. It transformed Latin America into a backyard where military and economic intervention was naturalized, a logical extension of continental conquest onto a hemispheric stage.

The White Man’s Burden provided the humanitarian gloss for overseas empire, framing the brutal colonization of the Philippines and Puerto Rico as a noble, sacrificial duty to civilize “sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child.” It was the export of a domestic ideology, declaring entire populations unfit for self-rule—the same belief that undergirded slavery at home.

These were not fringe ideas but the central engines of national policy, creating a powerful national identity where whiteness was synonymous with sovereignty, virtue, and the right to dominate.

The Great Mis-Education: A Mythology of Innocence

How, then, does a nation built on such explicit racial hierarchy produce citizens who recoil at the explicit racism of a Trump rally? The answer lies in a profound and intentional mis-education.

The American creed presented in textbooks and national myth is a carefully curated edit. It is a story of democracy and liberty, of Pilgrims and pioneers, that systematically decouples these ideals from the racial tyranny that financed and facilitated them. The genocide of Indigenous peoples is minimized to “conflict” or “westward expansion.” The enslavement of millions is segregated into a single tragic chapter, rather than understood as the engine of early American capital. Imperial conquests are framed as benevolent “foreign policy.”

This creates a duplicitous national consciousness. Americans are taught to venerate the Declaration of Independence’s promise of equality while being insulated from the fact that its principal author and most early beneficiaries envisioned that equality exclusively for white men. We celebrate a “melting pot” culture—shaped by Indigenous, African, Latin American, and Asian influences—while the political power to define the nation has been fiercely guarded as a white prerogative. This selective history is a powerful anesthetic. It allows generations to inherit the privileges of a racial caste system while believing fervently in their own nation’s inherent innocence and moral exceptionalism. It makes racism seem like a deviation, a “sin” we are overcoming, rather than the core organizing principle we have continuously refined.

Trump: The Unvarnished Tradition

Donald Trump’s political genius—and his profound traditionalism—lies in his rejection of the anesthetic. He does not traffic in the coded “dog whistles” of late-20th-century politics; he uses a bullhorn, reactivating the unfiltered language and logic of America’s racial id.

His rhetoric is a direct echo of past doctrines. Labeling Mexican immigrants “rapists” and “animals” and African nations “shithole countries” is the dehumanizing language of Manifest Destiny and the White Man’s Burden, applied to modern migration

. His central promise of a “big, beautiful wall” is a 21st-century racial frontier, a physical monument to the belief that the national body must be purified of non-white “infestation.”

Table: The Ideological Lineage from Doctrine to Trump

| Historical Doctrine | Core Racial Logic | Modern Trump-Era Manifestation |

| Manifest Destiny | Divine right to displace “savage” non-white peoples from desired land. | The border wall as a new frontier; rhetoric of immigrant “invasion” and “infestation.” |

| Monroe Doctrine | Hemispheric dominance and paternalistic intervention over non-white nations. | “America First” isolationism that rejects multilateralism while asserting unilateral military/economic power. |

| White Man’s Burden | The “civilizing” mission justifies domination over supposedly inferior peoples. | Framing immigration bans and harsh policies as protecting American civilization from “shithole countries.” |

His policies operationalize this ideology. The Muslim Ban, the crushing of asylum protocols, and the threat to end birthright citizenship are not simply strict immigration measures; they are efforts to legally redefine who belongs to the American nation along racial and religious lines. His administration’s systematic rollback of civil rights protections, from voting rights to LGBTQ+ safeguards, and its dismantling of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs are a direct assault on the fragile infrastructure of multiracial democracy built since the 1960s.

Most tellingly, his adventurous and aggressive militarism—from threatening “fire and fury” against North Korea to deploying federal troops against predominantly Black cities like Washington D.C. and Chicago under the pretext of crime emergencies—reveals the intrinsic link between white supremacy at home and imperial aggression abroad. As academic research confirms, support for militarized foreign policy among white Americans is strongly correlated with racial resentment, viewing non-white nations and peoples as inherent threats or legitimate targets for domination. Trump’s “America First” bellicosity is not an isolationist retreat but a reassertion of a racialized nationalism that sees the world as a hostile arena of competition against lesser peoples.

The Second Backlash and the Crisis of White Identity

Trumpism is the vehicle for a second great white backlash, a historical bookend to the first backlash that destroyed the multiracial democracy of Reconstruction after the Civil War. That first backlash, powered by the Klan, “Lost Cause” mythology, and Northern complicity, re-established white rule through terror and Jim Crow.

The current backlash, ignited by the Civil Rights Movement and supercharged by the election of Barack Obama, seeks to roll back the democratic gains of the past sixty years. Its fuel is white grievance—a pervasive fear among some white Americans that demographic change and racial equity represent a loss of status, a zero-sum dispossession . Slogans like “Take Our Country Back” and the defensive cry of “All Lives Matter” are the modern lexicon of this backlash, inverting reality to frame the pursuit of equality as an unfair attack on a threatened majority

.This is the source of the anguish for well-intentioned white Americans. They were raised on the edited, duplicitous creed. They believed in a forward-moving arc of progress. To see the naked brutality of racism not only re-emerge but be cheered from the highest podium shatters that narrative. The difficulty is in reconciling their own identity with the realization that the “greatness” many are nostalgic for was, for others, a regime of explicit subjugation. It is the pain of realizing that the comforting national myth is a lie, and that a more honest, more brutal history is demanding reconciliation.

Conclusion: Facing the Unbroken Line

Donald Trump is a classic American figure because he channels the nation’s most enduring political tradition: the mobilization of white racial anxiety to consolidate power and resist the expansion of a truly pluralistic democracy. He has ripped away the veneer of the mis-educating myth, revealing the unbroken line from the Puritan city on a hill to the MAGA rally.

To argue that this is not “real” America is to indulge in the very fantasy that enabled it. Racism and white supremacy are not un-American; they are as American as apple pie, woven into the fabric of our institutions, our geography, and our national story. The democratic ideals we rightly cherish have always coexisted in tension—and often in outright conflict—with this hierarchy. The struggle of the 21st century is not to defeat a foreign intrusion, but to finally sever this entrenched lineage. It begins by abandoning the comforting lie of national innocence and confronting, at last, the difficult truth of who we have been, and therefore, who we risk remaining.