By Delgreco Wilson

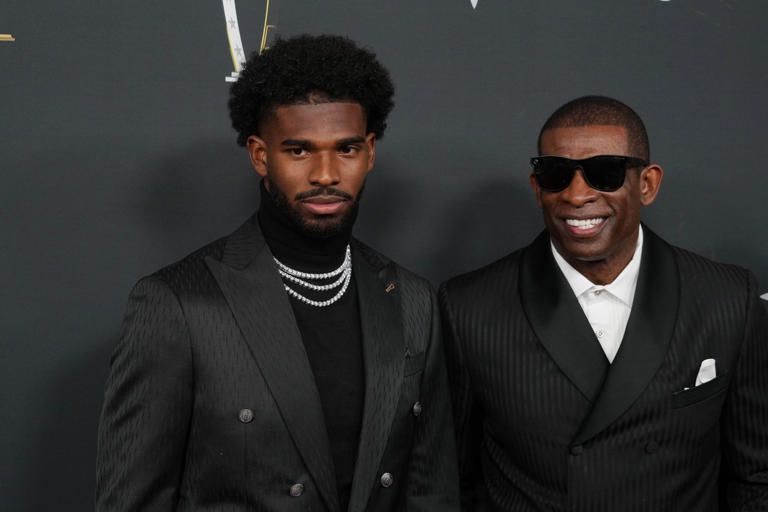

CAMDEN, NJ – In the high-stakes arena of American sports, where we claim to celebrate grit and triumph, we are witnessing the rise of a new generation of Black athletes who embody a potent, unyielding confidence. Angel Reese, the WNBA and former LSU basketball star known as “Bayou Barbie,” and Shedeur Sanders, the Cleveland Browns rookie and former star quarterback for his father Deion’s Colorado Buffaloes, are not just exceptional talents; they are cultural phenomena.

Their athletic prowess is undeniable, record-breaking, and thrilling. Yet, for all the celebration, a palpable undercurrent of disdain follows them. The comment sections boil over with vitriol; sports talk radio callers huff about “arrogance”; and a certain segment of the populace seems genuinely unnerved. To understand this visceral response, we need to excavate a term from the ugliest chapters of the American lexicon: the “uppity Negro.” While the phrase itself is now largely relegated to the shadows, the social control it represents is very much alive, and it is the most potent framework for understanding the backlash against these two young Black icons.

The Ghost in the Stadium: A History of “Uppity”

The word “uppity” is an old English adjective for someone putting on airs above their station. But in the American context, particularly in the antebellum South and the Jim Crow era, it was weaponized into a specific and terrifying racial slur. White supremacy required a rigid social hierarchy where Black people were expected to perform subservience—to be grateful, obedient, and to never, ever challenge their “place.”

An “uppity Negro” was anyone who violated this unwritten code. The crime wasn’t just success, but any behavior that suggested equality: a Black man owning a successful farm, a Black person speaking without the obligatory “sir” or “ma’am,” dressing well, or—most fundamentally—looking a white person in the eye with unflinching self-assurance. The accusation of being “uppity” was a tool of enforcement. It was a warning and a justification for punishment, a linguistic precursor to social ostracization, economic retaliation, or far, far worse. It was the mechanism for maintaining a caste system.

In the modern era, the explicit phrase is (mostly) taboo, but its spirit thrives in coded language. When a Black person in the public sphere is called “arrogant,” “cocky,” or “angry,” or when their achievements are dismissed as a product of “affirmative action” or mere nepotism, they are being subjected to the modern “uppity” accusation. The underlying message is unchanged: You are transgressing an unspoken social boundary.

A New Vanguard: The Unapologetic Reign of Reese and Sanders

Enter Angel Reese and Shedeur Sanders. Their rise has been rapid, dramatic, and steeped in a self-belief that refuses to be quiet.

During LSU’s 2023 national championship run, Angel Reese became a national lightning rod. After hitting a game-sealing shot, she famously trailed her opponent, pointing to her ring finger—a gesture signaling where her championship ring would go. The celebration was branded “classless” and “disrespectful” by many, while similar antics from white male athletes are often celebrated as “competitive fire.” Reese, a young Black woman, was not conforming to the passive, grateful archetype often demanded of her. She was, in the historical sense, refusing to perform subservience. She was owning her moment with a theatrical flair that said, “I belong here, and I will celebrate as I see fit.”

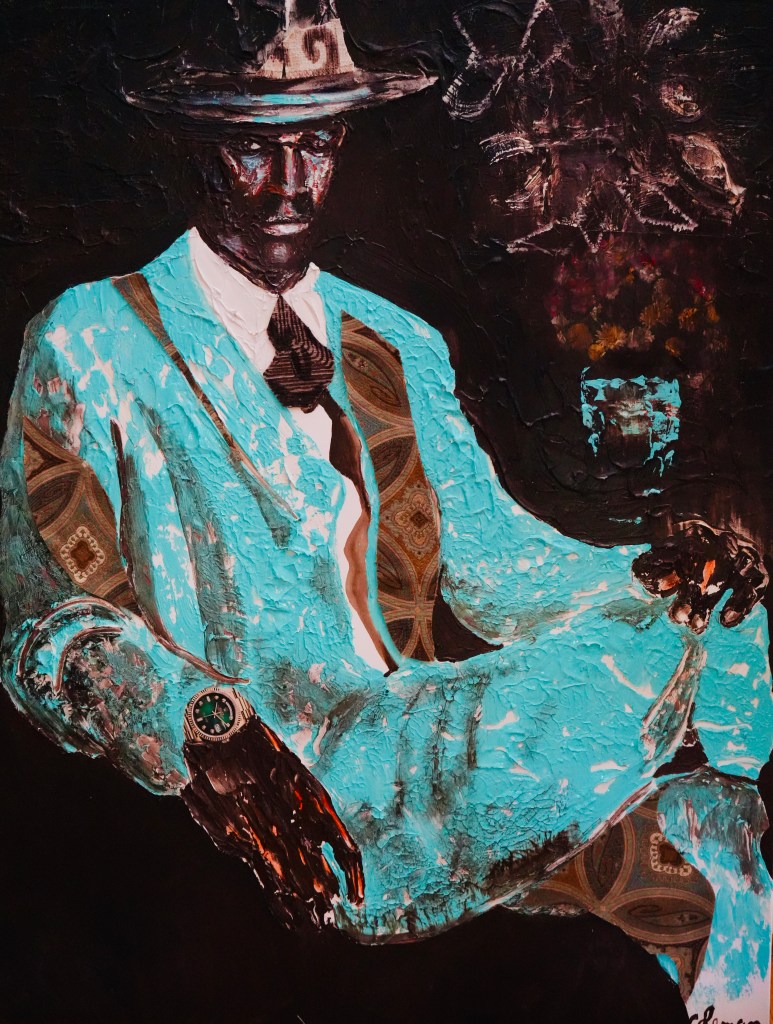

Shedeur Sanders’ confidence is of a different, but equally potent, strain. As the quarterback and son of Coach Deion Sanders, he operates with a preternatural calm and an unshakable belief in his own ability. He carries himself with the polish of a CEO, his demeanor often cool and unbothered even under extreme pressure. This is not the “grateful-to-be-here” athlete. This is an athlete who expects to win. When he led a last-second, game-winning drive against Colorado State, his post-game comment was not one of relief, but of expectation: “It’s just a regular operation, you know? We do it in practice all the time.” For critics, this isn’t seen as poise, but as arrogance. He is not waiting for permission to be great; he simply assumes it.

The Root of the Discomfort: A Challenge to the Racial Order

So why does this confidence cause such disconcerting feelings among many white Americans? The reasons are buried deep in the national psyche.

First, it is a direct challenge to white supremacy and entitlement. The ideology of white superiority depends on Black inferiority. An unapologetically confident, successful Black person who does not seek approval or defer to white sensibilities shatters this foundational myth. It challenges an unearned sense of entitlement to social deference.

Second, it creates profound cognitive dissonance. For generations, racist stereotypes have depicted Black people as lazy, ignorant, or simple. Figures like Reese and Sanders—articulate, strategic, and dominant—force a confrontation with these stereotypes. The easiest psychological escape from this dissonance is not to abandon the stereotype, but to pathologize the individual as an exception who is “getting above themselves.”

Finally, it represents the erosion of a controlled identity. The “uppity” Black athlete is the antithesis of the “good Negro”—the humble, non-threatening, and subservient figure who “knows his place.” By defining their own identities—Reese with her “Bayou Barbie” glamour and trash-talk, Sanders with his CEO cool—they refuse to be controlled by white expectations. This act of self-definition is, in itself, a radical and threatening act in a framework built on their subjugation.

A Playbook for the Next Generation

For young Black athletes who will inevitably find themselves navigating these same treacherous waters, the path forged by Reese and Sanders, though rocky, provides a crucial blueprint.

- Own Your Narrative. Do not let others define you. Angel Reese leaned into the “Bayou Barbie” persona, turning criticism into a brand of empowerment. Control your story on social media and in interviews.

- Let Your Work Ethic Be Your Shield. The most unassailable defense is undeniable excellence. The vitriol aimed at Shedeur Sanders often evaporates in the face of a perfectly thrown fourth-quarter touchdown. Performance can silence critics when logic and reason cannot.

- Find Your Community and Mentors. The weight of this scrutiny is immense and unfair. Building a support system of family, trusted coaches, and peers who understand the unique pressures of being a Black athlete in the public eye is non-negotiable for mental and emotional survival.

- Understand the History. Knowing that the backlash is not really about you, but about a deep-seated historical anxiety, can be a source of strength. You are not the problem; you are confronting a legacy of control that long predates you.

The visceral response to Angel Reese and Shedeur Sanders is not a simple story of sports rivalry or personal dislike. It is a modern manifestation of an ancient American anxiety. Their confidence is interpreted as a threat because it is one—a threat to a racial hierarchy that has, for centuries, demanded Black submission. They are not just playing games; they are, with every pointed finger and coolly delivered quote, expanding the boundaries of what a Black athlete is allowed to be. And in doing so, they are forcing America to confront the ghost in its stadium.